1. People in Poor Health: who are we concerned about?

People in poor health are more sensitive to the impacts of climate change and extreme weather events

Credit: ©iStock/monkeybusinessimages

On this page:

Introduction

The impacts of climate change and extreme weather events can affect anyone, but those already in poor health potentially face more serious harm. Not all individuals in poor health are equally sensitive or equally vulnerable; different conditions may mean people are affected in different ways. Some people may also be more vulnerable due to other social or environmental factors. People experiencing multiple causes of vulnerability are the most extremely socially vulnerable.

The sensitivity of people in poor health to climate impacts can be compounded by other characteristics, such as age. Older people and babies/young children, for example, are particularly sensitive to extreme weather. Social factors also affect the ability of people to adapt to climate impacts and extreme weather events, including being on a low income, being a tenant, being socially isolated or living in certain types of housing. The Further Resources section provides a link to where you can get more information about who is socially vulnerable and why.

The following section shows how ill-health can make people particularly sensitive to climate impacts and related extreme weather. It should be noted that the specific vulnerabilities of individuals and communities will be affected by other personal, environmental and social factors which are explored in detail elsewhere in this website.

Groups sensitive to heatwaves

People with pre-existing health problems may be more likely to experience detrimental physical impacts such as dehydration during a heatwave event.1,2 Particular health problems of concern include chronic cardiovascular, respiratory illness, diabetes, renal diseases, nervous system disorders, Parkinson’s disease, emphysema and epilepsy. Furthermore, people who already have a high body temperature, for example as a result of an infection, are more susceptible to the effects of heat.

People with limiting long term illness may have diminished ability to adapt to high temperatures due to lower awareness of their circumstances or an inability to take action.3 Examples of people who may be disproportionately affected include people who are bed-bound, unable to leave home daily, or who are unable to care for themselves for other reasons.

People with mental health disorders may not be able to cope with extreme heat or alter their physical environment when hot.4 People affected by mental health issues may be less likely to take effective precautions, recognise the symptoms of heat stress such as dehydration or know what to do in response. In addition, there is evidence that certain medications for the treatment of mental health conditions can make people more susceptible to the effects of heatwaves.5,6

People on medications that affect the body’s ability to sweat (renal function) or to perform its other normal temperature regulation functions will be more susceptible to the effects of heat.7 The National Health Service provides guidance on the medicines which can cause problems for patients during heatwaves,8 in addition to those associated with the treatment of mental health conditions.

Those in care homes are more reliant on others to deal with high temperatures. There is an association between dependency and the potential for adverse effects from heatwave events.9,10 Care home residents may experience greater exposure to heatwave events if indoor temperatures are not appropriately controlled or moderated, sufficient refreshments provided, and account taken of the different temperature preferences of residents.11 Institutional regimes can also exacerbate problems through being too rigid or due to difficulty in satisfying all of a building’s users’ needs, including staff.12,13 This underlines that it is not just the most fragile and dependent people within residential and care homes that require support during extreme weather events like heatwaves. Evidence suggests that some of the most independent and least physical fragile can be disproportionately affected, potentially as a result of staff concentrating on the most dependent residents and a lack of knowledge about symptoms and appropriate actions amongst the more independent residents.14,15

People who misuse alcohol or take illicit drugs may be unable to adapt quickly and be less likely to follow public health announcements during extreme weather events.16

People who are homeless tend to have higher rates of ill-health compared to other people and a greater susceptibility to the effects of heatwaves. Homeless people tend to have higher rates of physical and mental illness, a greater difficulty in effectively managing illness and an increased likelihood to have substance dependencies and cognitive impairments. Homeless people also have other environmental and social factors which increase their vulnerability. They tend to be more exposed to heatwaves through spending a greater amount of time outdoors, often in urban areas where temperatures are higher. See the sections on Adapting Buildings and Green Infrastructure on how to address issues in the built and natural environment. Homeless people are also often socially isolated so are less likely to receive help if suffering from the effects of heat stress. As a result, heatwaves can cause mortality, a worsening of existing illness or lead to other forms of ill-health in this group. See the Heatwave Plan for England.

Groups sensitive to flooding

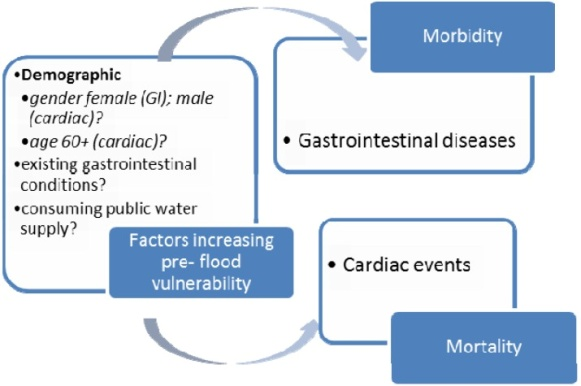

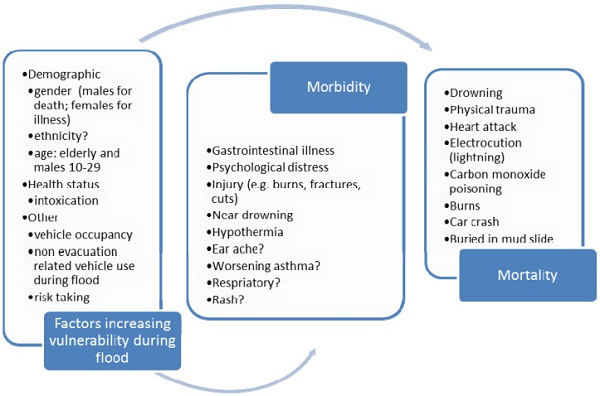

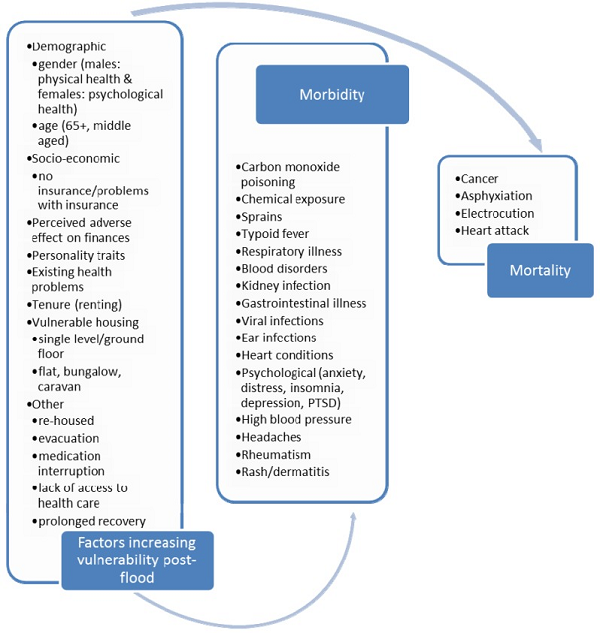

There are direct and indirect health impacts from flooding.17,18 A broad range of possible flood-related health outcomes can affect people before, during and after events (Figure 1). Their relative importance depends on the nature of the flooding itself, behavioural responses to it and a range of other environmental, social and personal risk factors, including pre-existing illnesses.19

Figure 1: Health outcomes associated with flooding, before (top) during (middle) and after (bottom).20

People who are temporarily or permanently ill are one of the groups expected to require specific help during a flood event. The National Flood Emergency Framework for England also highlights other groups including: children; older people; pregnant women; people with physical, sensory and cognitive impairments; homeless people; tourists; and people from different cultural and language backgrounds.21 Further Resources (in Section 6 above) has more information about some of these other groups.

Flooding may restrict an individual’s access to medicine, e.g. due to loss or damage, and make it difficult to obtain appropriate medical attention in an emergency. Flood events can directly impact local medical services and also affect the wider community given than it may be necessary for hospitals to postpone routine or other non-urgent medical treatments.22

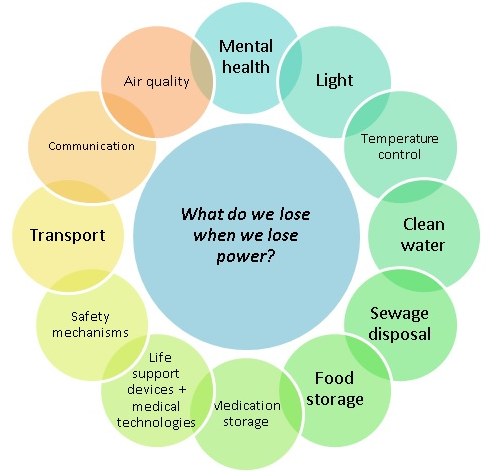

People with limiting long term illnesses can be less able to prepare for, cope during and recover from flooding. Vulnerability can be particularly high during events; for example, power-cuts can impact on life support equipment, such as oxygen generators or ventilators, or affect people’s mobility given that they may be reliant on electric wheelchairs requiring recharging and/or access to lifts.23 Taking preparatory action is particularly important as more complex health care is now being delivered at home rather than in hospitals and medical centres often using more sophisticated and power-reliant equipment.24 Power cuts can also affect other services and be an outcome from heat-related events as well as flooding and other hazards like storms (Figure 2). The use of alternative energy sources, like inefficient or poorly managed generators can lead to other impacts, such as carbon monoxide hazards.25,26 Accessing clean drinking water may also present particular challenges for this group as is access to a water supply for people on home kidney dialysis. Those living with mental or physical disabilities require additional assistance in preparing for and recovering from flood events. However, these impacts are not just felt by individuals; the presence of a disabled family member puts additional pressures on others in households affected by extreme events and the recovery of these households may take longer.

People with mental health disorders may be less able to prepare for and respond to flooding. Conditions such as dementia or Alzheimer’s can change how a person views the dangers associated with a flood event and how they behave in response.27 Ad-hoc carers helping people during or immediately after events may not have sufficient information about an individual’s medical history and associated medical and care needs28 and not all vulnerable people are able to provide appropriate information to carers under these circumstances.

People who misuse alcohol or take illicit drugs may be unable to adapt quickly and be less likely to follow public health announcements during extreme weather events.29

Figure 2: The direct and indirect impacts of power cuts on different aspects of health and wellbeing.30

References

- Kovats, R.S., Hajat, S., and Wilkinson, P. (2004) Contrasting patterns of mortality and hospital admissions during hot weather and heat waves in Greater London, UK. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 61(11): 893-898.

- McGeehin, M.A. and Mirabelli, M. (2001) The potential impacts of climate variability and change on temperature-related morbidity and mortality in the United States. Environmental Health Perspectives 109(supplement 2): 185-189.

- Defra (2012) UK Climate Change Risk Assessment: Evidence Report, London

- Reinhard, K., Rubin, C., Henderson, A., Wolfe, M., Kieszak, S., Parrott, C., Adcock, M. (2001) Heat-Related Death and Mental Illness During the 1999 Cincinnati Heat Wave. The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology 22(3): 303-307

- Page, L. A., S. Hajat, R. S. Kovats and L. M. Howard (2012). "Temperature-related deaths in people with psychosis, dementia and substance misuse." Br J Psychiatry 200(6): 485-490.

- Bouchama A, Dehbi M, Mohamed G, Matthies F, Shoukri M, Menne B. Prognostic factors in heat wave related deaths: a meta-analysis. Archives of internal medicine. 2007 Nov 12;167(20):2170-6.

- Defra (2012) UK Climate Change Risk Assessment: Evidence Report, London

- NHS (2012) Which medicines could cause problems for patients during a heatwave?

- Kovats, R.S. and Ebi, K.L. (2006) Heatwaves and public health in Europe. European Journal of Public Health 16 (6): 592-599

- Poumadere, M., Mays, C., Le Mer, S. and Blong, R. (2005) The 2003 Heatwave in France: Dangerous Climate Change Here and Now Risk Analysis 25(6): 1483-1494

- Defra (2012) UK Climate Change Risk Assessment: Evidence Report, London

- Building comfort for older age: Designing and managing thermal comfort in low carbon housing for older people.

- Stafoggia M et al. (2008). Factors affecting in-hospital heat-related mortality: A multi-city case-crossover analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62:209–215.

- Brown, S. and G. Walker (2008). "Understanding heat wave vulnerability in nursing and residential homes." Building Research and Information 36(4): 363-372.

- Anderson, M., C. Carmichael, V. Murray, A. Dengel and M. Swainson (2012). "Defining indoor heat thresholds for health in the UK." Perspect Public Health.

- Defra (2012) UK Climate Change Risk Assessment: Evidence Report, London

- World Health Organisation Europe (2013) Floods in the WHO European Region: health effects and their prevention

- Defra (2013) The National Flood Emergency Framework for England

- Lowe, D., Ebi, K.L. and Forsberg, B. (2013) Factors Increasing Vulnerability to Health Effects before, during and after Floods Int J Environ Res Public Health. 10(12): 7015–7067

- Lowe, D., Ebi, K.L. and Forsberg, B. (2013) Factors Increasing Vulnerability to Health Effects before, during and after Floods Int J Environ Res Public Health. 10(12): 7015–7067

- Defra (2013) The National Flood Emergency Framework for England

- Fernandez, L.S., Byard, D., Lin, C-C., Benson, S. and Barbera, J.A. (2002) Frail elderly as disaster victims: emergency management strategies. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 17(2): 67-74

- Fernandez, L.S., Byard, D., Lin, C-C., Benson, S. and Barbera, J.A. (2002) Frail elderly as disaster victims: emergency management strategies. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 17(2): 67-74

- Klinger C, Landeg O, Murray V. Power Outages, Extreme Events and Health: a Systematic Review of the Literature from 2011-2012. PLOS Currents Disasters. 2014 Jan 2. Edition 1

- Lowe, D., Ebi, K.L. and Forsberg, B. (2013) Factors Increasing Vulnerability to Health Effects before, during and after Floods Int J Environ Res Public Health. 10(12): 7015–7067

- Klinger C, Landeg O, Murray V. Power Outages, Extreme Events and Health: a Systematic Review of the Literature from 2011-2012. PLOS Currents Disasters. 2014 Jan 2. Edition 1

- Defra (2012) UK Climate Change Risk Assessment: Evidence Report, London

- Fernandez, L.S., Byard, D., Lin, C-C., Benson, S. and Barbera, J.A. (2002) Frail elderly as disaster victims: emergency management strategies. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 17(2): 67-74

- Defra (2012) UK Climate Change Risk Assessment: Evidence Report, London

- (note permission required) Klinger C, Landeg O, Murray V. Power Outages, Extreme Events and Health: a Systematic Review of the Literature from 2011-2012. PLOS Currents Disasters. 2014 Jan 2. Edition 1

Built by:

© 2014 - Climate Just

Contact us