As well as being more susceptible to harm due to their age, older people are often associated with other characteristics which increase their vulnerability to climate impacts.

Credit: JRF/Jo Hanley

On this page:

The impacts of climate change and extreme weather events can affect anyone, but older people potentially face more serious harm. There is conclusive evidence that when compared to other adults, older people - those over 65, but particularly people over 75 - consistently face more severe impacts as a result of flooding and heatwaves1,2. This is partly due to the tendency for older people to be more biophysically susceptible3. However, older people may also be associated with a range of other characteristics which increase their vulnerability, such as being socially isolated, being in ill-health, having lower personal mobility, living in certain types of housing or being on a low income4,5. Although in 2011/12 pensioner poverty reached a 30-year low6, some pensioners are still living on low incomes, with older pensioners and single female pensioners having the lowest average incomes within the pensioner group7. For these reasons, older people are highlighted as a key focus for climate adaptation policies and plans8,9.

While older people are generally more socially vulnerable than other adults, not all older people are equally sensitive or equally vulnerable. Although evidence often relates to chronological age, there are huge differences between people in the same age group as a result of varying biological, social and psychological factors10. For example, the different personal characteristics of older people such as their health can influence the extent to which they are sensitive to climate impacts and extreme weather. Similarly, social characteristics, such as income11 and mobility, vary greatly11. This means that some older people have a considerably lower capacity to adapt than others. Older people experiencing multiple causes of vulnerability are the most socially vulnerable. However, a person’s vulnerability is not a static characteristic and will change as personal circumstances change over time. As with all people, the impacts of a particular event on an older person will therefore depend on how different circumstances happen to interact at the time that this occurs12. For this reason it is useful to understand the range of factors which can influence a person’s vulnerability and the extent to which they are likely to occur in particular neighbourhoods. (See Which places are disadvantaged?)

Older people may be less likely to seek assistance than people in other groups13. Some older people can be socially isolated from the rest of the community that they live in or have other reasons not to seek help from authorities and service providers. For example, they may fear disruption to routines, losing their homes due to being seen as unable to cope alone, or losing independence and control14. However it is wrong to presume that this applies to all older people or that older people are necessarily passive or disengaged when it comes to environmental or climate change issues15. Some forms of participation can be quite common in older groups. For example, more than a quarter of over 65 year-olds participate in voluntary work or work in the wider community16. While this doesn’t necessarily mean that they are more likely to seek assistance, the improved social connections this brings may mean that they are more likely to be offered help and, potentially, more likely to accept it. However, evidence also shows that people tend to feel more comfortable offering help and less comfortable about accepting it from others, particularly where such help is perceived negatively, for example, in terms of personal autonomy and independence17.

Older people can be more likely to live in particular types of housing which may increase their exposure to heatwaves and floods. Retirement developments tend to be single level apartments or bungalows developed to better meet the day-to-day needs of older residents18. Such single level dwelling types are favoured by older people more generally19. However, people living in these homes are potentially more likely to be affected by the loss of possessions, including essential equipment, due to the higher likelihood of them being damaged in floods, compared to people where possessions can be stored in upper floors. While newer developments may be more likely to have flood adaptation measures in place, the availability of such measures does not guarantee that they will be used, or used correctly. For example, studies into the use of energy efficiency measures have shown how these sorts of adaptations are not always used as intended20. Furthermore, some residential buildings accentuate the impacts of extremely hot, or indeed cold, conditions. To help further understand the problem of overheating in residential buildings, the 2014/15 English Housing Survey will collect explicit data from building occupants21. See the Adapting Buildings section for more information about the effects of building types and actions which can be taken.

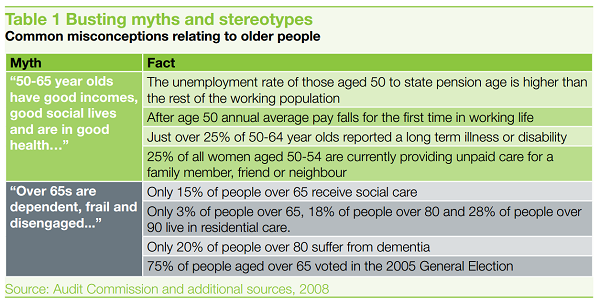

The following sections show how older people are likely to be more sensitive and vulnerable to climate impacts and related extreme weather than other adults. Although the focus is on heatwaves and flooding, it is important to stress that this group is also sensitive to disproportionate impacts from a range of other climate and environment related hazards such as air pollution (which can also be connected to heatwaves22,23), drought, cold weather, food- and water-borne diseases and UV radiation24. Although the potential for extreme impacts is emphasised, older people are an extremely diverse group with people of very different vulnerability profiles, not all of which are a simple function of age (Figure 1). It is therefore highly likely that local adaptation and adaptation-related measures will need to include a suite of different responses in order to maximise people’s ability to help themselves, while protecting the most acutely vulnerable.

Figure 1: Examples of possible misconceptions about older people.25

There is strong national and international evidence about the greater likelihood for older people to be affected by heatwaves.26

The largest proportion of the 2,000 excess deaths in England and Wales during the August 2003 heatwave occurred in people who were over 75, and in London this group also had an increased rate of hospital visits.27 Similar evidence has been found elsewhere. Analyses of the effects of the 2003 heatwave in other European countries28 and the impacts of other heatwaves in Europe and the United States29,30 have all found that older people were a particularly vulnerable group.

Older people may be more likely to experience detrimental physical impacts such as dehydration and the worsening of symptoms of existing health problems such as respiratory illness and heart disease during a heatwave.31,32,33 There are biophysical differences between older people and other adults which make temperature regulation processes less efficient in this group, something which is important in terms of people’s ability to cope with extremes of cold as well as heat. Difficulties coping in heatwaves can be particularly marked when older people have other health problems which also affect thermo-regulation, such as chronic cardiovascular, respiratory illness, diabetes, renal diseases, nervous system disorders, Parkinson’s disease, emphysema and epilepsy.34 Furthermore, people who already have a high body temperature, for example, as a result of an infection, are more susceptible to the effects of heat.

Some older people may also have diminished ability to adapt to high temperatures due to lower awareness of their circumstances or an inability to take action.35 Some older people may be bed-bound, unable to leave home daily, or unable to care for themselves for other reasons, such as through living with dementia or other degenerative illnesses.

Older people in residential or nursing homes are more reliant on others to deal with high temperatures and older people in hospitals and care homes tend to be disproportionately affected by heatwave events.36 There is an association between dependency and the potential for adverse effects from heatwave events.37,38 (see also People in poor health) Older people living in care homes are more likely to have physical or mental health problems, which can make them more sensitive and less able to adapt to high temperatures.39 Often the perceived thermal needs of the frailest residents dictate how specialist buildings are designed and operated, but this can negatively affect other residents.40 This is especially problematic where the different temperature preferences and related needs of residents cannot be accommodated, for example, through appropriately adaptable heating/cooling systems which allow rooms to be kept at different temperatures, or the flexible provision of cool refreshments.41,42 Institutional regimes can also exacerbate problems through being too rigid or due to difficulty in satisfying all of a building’s users’ needs, including staff.43

Older people may not appreciate their increased susceptibility to heat or consider high temperatures to be a particular problem.44 A survey of 456 older people in Islington suggested that respondents were more likely to welcome hot weather than not.45 This was despite over half of the respondents having personal health or mobility characteristics which could affect their ability to cope. The survey emphasised how council or voluntary services may be particularly important to older people who lack social and support networks, particularly family, as an initial source of help. Although only 13.5% stated that they did not have any social support networks, 17.5% of those interviewed said that they would not approach anyone for help during a heatwave. See Islington’s case study for more information.

Older people may be reluctant to take recommended actions to cool their homes, such as leaving windows open at night. Interviewees in Islington identified neighbourhood noise and fear of crime as key reasons for failing to open windows at night.45 Even where buildings are well adapted or have retrofit measures in place, they may not be used as designers intended.46

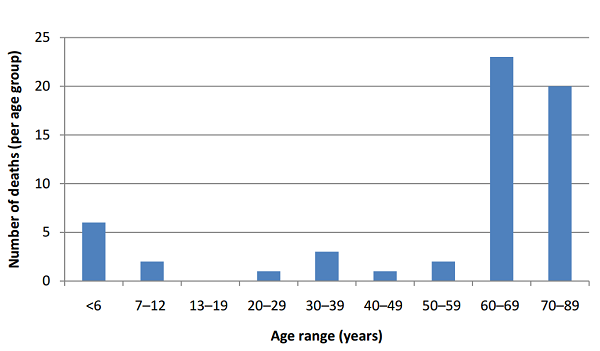

Floods affect the health and wellbeing of older people in multiple direct and indirect ways. Older people tend to experience greater impacts from flood events, a greater incidence of flood-related disease (for example, associated with contaminated water) and higher rates of mortality.47 Analysis of the impacts of the 1953 floods (Figure 2) highlight higher mortality rates among older people than other age groups and also show that this can result from secondary health impacts, such as hypothermia and heart problems, as well as from drowning. Flooding may also restrict an individual’s access to medicine, or make it difficult to obtain appropriate medical attention in an emergency. Flood events can directly impact local medical services and also affect the wider community, given than it may be necessary for hospitals to postpone routine or other non-urgent medical treatments.48

Figure 2 Age distribution of flood-related mortality associated with the 31 January-1 February 1953 flooding at Canvey Island (Essex).49

Older people may be less able to prepare for and cope during flood events. They are less likely to respond to flood warnings50 and difficulties with balance, strength or mobility may make protecting homes from flooding or taking recommended measures more challenging.51 Vulnerability can be particularly high during events; for example, power-cuts can impact on life support equipment, such as oxygen generators or ventilators, or affect older people’s mobility given that they may be reliant on electric wheelchairs requiring recharging and/or access to lifts.52 Accessing clean drinking water may also present particular challenges for this group. Although mains water supplies are usually safe in flood events in the UK, older people can be more susceptible to any contamination of food or water due to less responsive immune systems.53 Older people are particularly reliant on personal aids such as glasses, dentures or hearing aids, which can become lost or damaged, making it difficult for them to cope.

Older people may find it particularly hard to recover from the effects of flooding. The stress of disruption and the loss of memorabilia can be devastating for older people, with many taking longer to recover compared to others, or never fully doing so.54 Flooding can cause a loss of confidence and a loss of memory for some, and pressures associated with taking in a displaced family member can cause social relationships to come under considerable strain.55 Some older people may find dealing with insurance claims and organising repairs challenging and some may even deny being affected.56 Effects can be exacerbated for people who are already in ill-health or who are socially isolated.

Older people living with mental health disorders may be less able to prepare for and respond to flooding. Conditions such as dementia can change how a person views the dangers associated with a flood and how they behave in response.57 Ad-hoc carers helping people during or immediately after events may not have sufficient information about an individual’s medical history and associated medical and care needs58 and not all vulnerable people are able to provide appropriate information to carers under these circumstances. For example, this may mean that people are unable to recall their full names and addresses59 and may become confused in unfamiliar surroundings.60

Back to the top